|

The Form: 1970–1979

author: Melody Sumner Carnahan

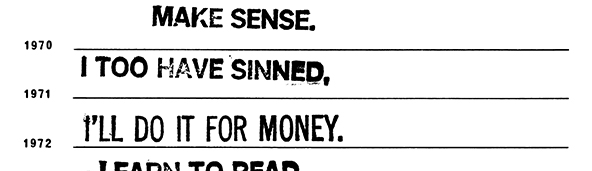

The book’s premise is what happens if you give someone a blank form with nothing but chronologically ordered years and empty spaces for comments and a signature? With the majority, it seemed the first inclination was to think, “What was I doing in those years?” The extension of this was, “What was happening in the world during these years?”

A few disregarded the dates, but were drawn to the format of the sheet itself—a blank space delineated with digits and parallel lines. We fill out many forms in a lifetime, and the practice is therefore familiar, even comfortable. Some filled out the blank lines as one would a grocery list. Others disregarded the dates yet neatly filled in the lines with poetry, an art whose parameters are loose enough to evade the sterility of the dates, lines, construct. There were those who did none of the above, either out of an aesthetic urge to do more (or less) or simply from a refusal to stay within the lines.

Von Minor assigns one word to each line; “system, serial, regiment, serial, series, sequence, successive, collate” in so doing, seems to be considering the formality of the chronologically ordered digits and their accompanying lines. Greg Nisotis chooses to fill his lines with various doodles, in which he appears disinterested at the structure imposed by the form. However, in Orwellian fashion, he enters his social security number in the space delineated for a signature. This is interesting because the inclusion of very personal data (a number) has the effect of feeling quite impersonal. John Cage’s response to the form also focuses on the digits, rewriting each year side by side with the original, in his own handwritten font.

Lark Drummonds, too, focuses on the chronology of years but this time in a more academic fashion: In addition to assigning grades in various places, as if the form were a test, she approaches the top of the form (1970-1979) as an equation, and then adds all the digits from 1970 to 1979 to get a sum of 19,745, finding the average to be 1974.5, a number no longer indicating a year due. Robert Ashley’s contribution also gravitated to the numerical aspect of the form, as he filled it in with a seemingly random collection of numbers, with the number 18 as his signature. This leads the viewer to conclude that Ashley either has an exceedingly dry sense of humor or that the meaning of his chosen numbers was based on an unknown formula.

Another dry but clever response came from James Dickey who pairs each year with a letter of the alphabet in ordinal fashion, beginning at 1970 with the letter “a” working his way down to the 10th letter of the alphabet (j), which he uses as the first letter of his signature. Richard Elmore took the form as a construct to the next level, breaking the space into a neatly patterned grid with the subcategories “women,” “work projects,” “experiences with significant emotional impact,” “places,” and “colors.”

Individual responses to the formality also included list-making—a seemingly instinctual reaction upon being presented with a nicely placed set of parallel lines. Some listed places, one listed her respective weights for each of the ten years; still others made seemingly arbitrary lists, such as hand-tied flies, punk bands, and Roman emperors.

While thinking about the most straightforward responses in which individuals approached the form I found myself contemplating how bizarre it is to see such a span of time (roughly 1/8th of the average life expectancy) condensed so easily, so simply in ten lines. Perhaps the more abstract responses and interpretations were an expression of being overwhelmed simply by the idea of trying to fit ten years of experience in such a small space—possibly a refusal to even attempt such a thing? I began thinking of my life—started imagining today/this week/this month/this year as something that could, in retrospect, be condensed equivalently. I found this unnerving. If I assumed my task was to subjectively describe ten years of experience, and only had ten lines upon which to accomplish this task, what would I include, and what would I leave out?

Also interesting is that for those who filled out the form during 1978, the tenth line, 1979, took on a different quality as an implication not of the past but the future. The responses were largely optimistic: “Approaching success!” “Happiness is just around the corner.” “Career on the upswing.” Understandably, we aren’t likely to fantasize about things getting worse. Despite this, Courtney Cook’s outlook for 1979 is quite dismal “WW III or depression.”

Working from a presupposition that the purpose of the form was to provide a description of individual experience over the course of a decade, it’s interesting how many people chose to mention their experiences in love, both positive and negative, as major milestones. The many contributions that include references to significant others force us to ask: “Do we define ourselves by who we’re with?”

Personally, one of the most intriguing aspects of this project was something that only dawned on me as I finished the book. The individuals who initially received the form were either friends, family, or artists that Carnahan respected. I might go so far as to presuppose that the participants in this project were generally chosen because she knew that the range of responses would be interesting, and furthermore, that particular responses were almost guaranteed to be interesting. These were all people who, in one way or another, were connected to the writer Carnahan through her own life experiences, even if she had never met them but simply appreciated a similar aesthetic. In this way, through collecting a multitude of statements made by family members, friends, acquaintances, and artists, she created her own expression of the decade.

—Brendan Bullock, writer and photographer, Santa Fe

|